Examine how social communication may affect everyday social interactions and/or academic performance as required by IDEA

Now part of the Video Assessment Tools platform

OVERVIEW

IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale (ages: 5-21) is an objective measure of social communication based on informal observations of clinicians, teachers, and parents. This tool aids in the clinical determination of a diagnosis/special education eligibility by examining how social communication deficits may affect everyday social interactions and/or academic performance (for educational planning purposes) (ages: 5-21) is an objective measure of social communication based on informal observations of clinicians, teachers, and parents. This tool aids in the clinical determination of a diagnosis/special education eligibility by examining how social communication deficits may affect everyday social interactions and/or academic performance (for educational planning purposes).

The IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale evaluates the impact of a child’s social communication on their social interactions, academic life, and home/after school life. The current rating scale asks parents, teachers, and clinicians to rate the various components of speech sound disorders on a 4-point scale (“never,” “sometimes,” “often,” and “typically”) and yields a percentile and standard score. By utilizing this rating scale, we are able to develop a better understanding of how a student’s social communication difficulties/differences may impact language development, as well as academic performance, and peer relationships.

Highlights

Helps measure impact on educational progress. Questions presented in a video based format. Automated scoring. Parents and teachers can easily access the rating forms online (by phone, tablet, etc). Parent Spanish forms and instructions included.

scores

Standard scores,

percentile ranks, impact analysis

ages

5-21 years

psychometric data

Nationwide standardization sample of 1006 examinees (typically developing), stratified to match the most recent U.S. Census data on gender, race/ethnicity, and region. Strong sensitivity and specificity (above 80%), high internal consistency, and test-retest reliabilities.

format

Online rating scale with accompanying videos that narrate and explain the questions. Automated scoring

Administration time

30 to 45 mins for all 3 rating scales

Examples of the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale Questions

Frequently asked questions

The nationwide standardization sample consisted of 1006 examinees (typically developing), stratified to match the most recent U.S. Census data on gender, race/ethnicity, and region.

YES, please follow the purchase order instructions on our site

The Impact Social Communication Rating Scale can be accessed as part of the Video Assessment Tools annual membership.

The IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale was developed at the Lavi Institute by Adriana Lavi, PhD, CCC-SLP (author of the Clinical Assessment of Pragmatics (CAPs) test, the Social Squad, the IMPACT Language Rating Scale, etc.

All standardization project procedures were implemented in compliance with the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education [AERA, APA, and NCME], 2014). Additionally, all standardization project procedures were reviewed and approved by IntegReview IRB (Advarra), an accredited and certified independent institutional review board, which is organized and operates in compliance with the US federal regulations (including, but not limited to 21 CFR Parts 50 and 56, and 45 CFR Part 46), various guidelines as applicable (both domestic and international, including but not limited to OHRP, FDA, EPA, ICH GCP as specific to IRB review, Canadian Food and Drug Regulations, the Tri-Council Policy Statement 2, and CIOMS), and the ethical principles underlying the involvement of human subjects in research (including The Belmont Report, Nuremberg Code, Declaration of Helsinki).

This is an online rating scale with accompanying videos that narrate and explain the questions. SLPs, teachers and parents are able to access the rating scale forms online. SLPs use automated scoring online to obtain standard scores and to generate a report.

Yes, please contact us to request a quote.

if you have further questions about our programs, please Contact Us

highlights of the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale

The results of the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale provide information on a student’s awareness of social context, intent to socialize, nonverbal language, social interactions, theory of mind, ability to accept change, social language and conversational adaptation, social reasoning, and cognitive flexibility. Data obtained from the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale is useful in determining eligibility criteria for a student with a social communication impairment.

Strong Psychometric Properties

The IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale was normed on a nationwide standardization sample of 1006 examinees. The sample was stratified to match the most recent U.S. Census data on gender, race/ethnicity, and region.

The IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale areas have strong sensitivity and specificity (above 80%), high internal consistency, and test-retest reliabilities.

Ease and Efficiency of Administration and Scoring

The IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale consists of three observational rating scales, one for clinician, one for parent, and one for the teacher. All IMPACT rating scales and scale converting software is available online. Rating scale item clarification videos are also provided on this website. Additionally, an instructional email with a link to the website and rating form is prepared for your convenience to send to teacher and parents.

Description of the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale

The IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale is a norm-referenced pragmatic language rating scale for children and young adults ages 5 through 21 years old. It is composed of 35-40 test items, and has three separate forms to be completed by clinician, parent(s), and teacher(s). It is an accurate and reliable assessment that yields valid results on informal observations of pragmatic language such as intent to socialize, nonverbal language (e.g., facial expressions, tone of voice), theory of mind, social reasoning and cognitive flexibility. Normative data of this test is based on a nationally representative sample of 1006 children and young adults in the United States.

Rating Areas

The test is composed of nine areas: social context, intent to socialize, nonverbal language, social interactions, theory of mind, ability to accept change, social language and conversational adaptation, social reasoning, and cognitive flexibility.

Testing Format

The IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale is composed of 35-40 test items. The test uses a series of items that asks the rater to score on a 4-point scale (“never,” “sometimes,” “often,” and “typically”). The rating scale yields an overall percentile and standard score. While completing this checklist, examinees are able to watch accompanying videos that will provide specific examples of what each question is asking. The videos are there to help examiners along if they have any questions regarding the skill that they are assessing.

Rating Scale Uses and Purpose

Parents and teachers provide us with invaluable information regarding a student’s social communication in both the classroom and in the home environment, however, this information is not always easy to obtain, explain, or understand. Additionally, the questionnaires, checklists, or surveys that we have used in the past may have overlooked or missed the specific areas of social communication (i.e., nonverbal language) we are currently hoping to address. The results of the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale test provide comprehensive information on pragmatic language skills and social language development of children and young adults. The scale provides natural and authentic observations by familiar observers across multiple settings and situations. The IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale can be a beneficial tool to support a referral, compliment other pragmatic language assessments, compare clinician’s, parent’s, and teacher’s ratings, help plan interventions, and monitor progress of interventions. By utilizing The Social Communication Rating Scale, we are able to develop a better understanding as to how a student’s pragmatic language skills may impact their academic performance and progress in school.

Code of Federal Regulations – Title 34: Education

34 C.F.R. §300.7 Child with a disability. (c) Definitions of disability terms. (11) Speech or language impairment means a communication disorder, such as stuttering, impaired articulation, a language impairment, or a voice impairment, that adversely affects a child’s educational performance.

The Individual’s with Disabilities Act (IDEA, 2004) states that when assessing a student for a speech or language impairment, we need to determine whether or not the impairment will negatively impact the child’s educational performance. In order to determine whether a pragmatic language impairment exists, we can collect parent, teacher, and clinician observations of the student in his/her home and educational environment, and analyze the impact of the impairment on academic success.

Importance of Observations and Rationale for a Rating Scale

Systematic observation and contextualized analysis is a form of informal language assessment that includes multiple observations across various environments and situations (Westby et al., 2003). According to IDEA (2004), such types of informal assessment must be used in conjunction with standardized assessments. Section. 300.532(b), 300.533 (a) (1) (I, ii, iii); 300.535(a)(1) of IDEA states that, “assessors must use a variety of different tools and strategies to gather relevant functional and developmental information about a child, including information provided by the parent, teacher, and information obtained from classroom-based assessments and observation.” Utilizing both formal and informal assessments is crucial in order to develop a whole picture of a child’s pragmatic language abilities. By observing a child’s pragmatic language skills via informal observation, examinees can observe key features of social language such as conversations, nonverbal language, and social reasoning. When we consider a clinician’s observations, we do not necessarily observe pragmatic language in everyday situations. Parent and/or teacher input may be beneficial during pragmatic language evaluation because it allows for the assessment to take place in an authentic setting and it is completed by someone who knows the child well and thus, is more likely to be a true representation of the child’s social communication skills (Volden & Phillips, 2010). The IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale provides us with both parent and teacher observation and perspectives of a child’s pragmatic language ability. When observing a child in their natural habitat, the observer gains a clear understanding of their child’s abilities across all domains of communication: form, content, and use. Additionally, many of the “abnormal communicative behaviors” that children with pragmatic impairments may demonstrate may be rare in occurrence (Bishop & Baird, 2001). When given the guidelines of what to look for, parents – who know their children the best – will more than likely be able to think of, and provide numerous examples of pragmatic language impairments. These pragmatic difficulties may not be so easily observed during clinical assessment and observation. Furthermore, it can be important to obtain information on how a child engages with their family, friends, and peers during familiar tasks in order to gain ecologically and culturally valid information on how a child functions and communicates on a day-to-day basis (Jackson, Pretti- Frontczak, Harjusola-Webb, Grisham-Brown, & Romani, 2009; Westby, Stevens, Dominguez, & Oetter, 1996).

During assessment and intervention planning, it is important to consider how social communication may adversely affect educational performance. Previous research has revealed that pragmatic language deficits can be expected to negatively impact a child’s social and emotional well-being (Schalock, 1996). For example, individuals with social communication impairment may participate in fewer peer interactions and are considered to be less preferred communication partners. Students with pragmatic language impairments may engage in less social behaviors such as sharing, cooperation, offering empathy, which are characteristics that have been linked to the development of peer relationships (Brinton & Fujiki, 2005; Hart, Robinson, McNeilly, Nelson, & Olsen, 1995). As a result, children and adolescents with pragmatic difficulties may have a difficult time creating and maintaining friendships. Those with pragmatic language difficulties may have trouble with the understanding, interpretation, and use of social language cues (both verbal and nonverbal) (Weiner, 2004). Additionally, students with social communication deficits may have difficulty with externalizing and internalizing behaviors which have been associated with poor academic performance, high rates of absenteeism, and low achievement (DeSocio & Hootman, 2004; Smith, Katsiyannis, & Ryan, 2011). Moreover, challenging behavior may be observed in children with severe communication impairments (Eisenhower, Baker, & Blacher, 2005; Kodituwakku, 2007). According to IDEA (2004), when a child’s behavior gets in the way of learning, the special education team must develop and recommend “positive behavioral interventions and supports” to be used in the school setting (IDEA, 2004: §300.324(a)(2)(i)).

Contextual Background for Rating Scale Areas

Difficulties in pragmatic language may include: turn-taking in conversation with a peer (e.g., asking questions, add-on comments), staying on topic, creating and maintaining friendships, introducing new/appropriate topics, understanding someone else’s perspective (theory of mind), accepting change, speech prosody (e.g., rising and falling of voice pitch and inflection), and the understanding and use of verbal and nonverbal cues (e.g., facial expressions, gestures, etc.) (Krasny, Williams, Provencal, & Ozonoff, 2003; Shaked & Yirmiya, 2003; Tager-Flusberg, 2003). The current assessment tool is composed of nine areas that address these key social language deficits. Table 1.1 reviews each area as well as provides an example test item taken from the assessment.

Awareness of Social Context evaluates a student’s ability to adequately and appropriately utilize introductions, farewells, politeness, and make requests. These forms of communication are described as essential and considered to be the building blocks to more complex language processes. When students begin to act in socially appropriate ways with teachers and peers, they are more likely to maintain attention when engaged in academic tasks (Eisenberg, Vallente, & Eggum, 2006).

Intent to Socialize takes a look at a student’s interest in interacting with peers, and seeking friendship or companionship. Peer relationships and friendships are critical to school and academic achievement for school-age children (Wentzel, Barry, & Caldwell, 2004; Newman Kingery, Erdley, & Marshall, 2011). Friendships are important in the development of social competences, as well as influencing children’s performance on classroom-learning activities, specifically those that involve collaboration and cooperation (Faulkner & Meill, 1993).

Nonverbal language evaluates a student’s ability to read micro-expressions and nonverbal language. Nonverbal cues, such as facial expressions, have a very important role in social interactions (de Gelder, 2006) and can be just as meaningful as spoken words. Often, nonverbal language can reveal how a person feels, although their verbal communication may be contradictory. An appropriate understanding of non-verbal language is critical in understanding another person, and in turn, it leads to an appropriate verbal response.

Social Interactions takes a look at a student’s active interactions with their peers, friends, and family. Children with language impairments tend to engage less in active interactions than typically developing peers, exhibit poorer discourse skills, and are less likely to offer socially appropriate verbal and nonverbal responses in conversations (Brinton, Fujiki, & McKee, 1998; Landa, 2005). Durkin and Conti-Ramsden (2007) compared friendship quality in 120 adolescents aged 16-years-old with and without SLI. Adolescents with SLI were found to exhibit poorer quality friendships. This study suggests that language difficulties (including social language deficits) may be predictive of poorer quality friendships, which in turn may impact academic success.

Theory of Mind evaluates a student’s ability to understand that other people have different perspectives than their own (e.g., different desires, wishes, and beliefs). Theory of mind is critical for social interactions beginning in early childhood and expanding until adulthood (Gweon & Saxe, 2013). The development of theory of mind is a cognitive milestone as well as a socio-emotional milestone that is essential for social language development and the ability to socially interact and understand others (Miller, 2009). Being able to understand the mind is crucial to the understanding and navigation of one’s social world.

Accepting Change assesses a student’s ability to accept modifications or changes to a plan. Changes of plans occur every day and when changes do occur students should respond in an appropriate manner/not have an extreme reaction. When students need constant reassurance after a change occurs, or he/she has a disruptive reaction, academic performance may be impacted.

Social Language and Conversational Adaptation evaluates a student’s ability to implement appropriate social communication skills during conversation. For example, a student should be able to stay on topic providing appropriate comments and questions. The student should be able to utilize appropriate eye contact, turn-taking, volume, and facial expressions. Additionally, the student should also be able to code-switch depending on who they are speaking with. For example, how a student talks to their peers will be different than how they speak to their teacher.

Social Reasoning assesses a student’s ability to see the “whole picture” or main idea. Sometimes students may have difficulty grasping key points, drawing conclusions and making other inferences from conversation, text, TV programs, and movies (Vicker, 2009). When students focus on irrelevant details, their academic performance can be impacted.

Cognitive Flexibility evaluates a student’s ability to come to terms with the amount of unfairness they observe in the world around them. For example, some students have a very hard time coming to terms with a situation if they view it as unfair or unjust. Students may become frustrated and appear persistent to make things “fair.” In order for students to demonstrate cognitive flexibility they must demonstrate awareness and adaptability.

Table 1.1 – Description of IMPACT Rating Scale Measures | |

Rating Scale Measure | Examples |

Awareness of Social Context Greets peers and staff (teachers, aides, etc.), checks-in with peers and seems aware of what peers are doing during class, recess, and lunch time | For example, when a student walks into class in the morning or after lunch, does he/she look around the room to see who is present, does he/she offer eye contact or smile when they see a friend, or a staff member. |

Intent to socialize Seeks companionship, friendship, attention, and daily interaction with peers; initiates interactions to gain attention; Engages in conversations and playful social exchanges; Able to initiate conversations and gain peers’ attention |

For example, before class begins, does the student engage in conversation with his/her peers? Does he/she talk about their weekend? Maybe a TV show from last night? During group projects, does the student speak and converse with other students? |

Nonverbal Language Uses facial expressions, tone of voice, and gestures to show emotions. |

For example, to demonstrate support/comfort to a peer, the student may frown his/her eyebrows to indicate empathy or disappointment, or the student may smile to share excitement. |

Social Interactions Appears to enjoy interactions with others. For example, the student shows interest in interactions during recess, lunch, and group projects |

The student may be seen with a group of students and engaging in conversation. The student may be participating with verbal comments, questions, as well as non-verbal language, such as smiling, laughter, etc. |

Theory of Mind Engages in pretend play during class activities (e.g., role playing or imaginative play) |

Student is able to role-play different scenarios or put themselves in “someone else’s shoes.” |

Rating Scale Measure | Examples |

Accepting Change Accepts changes in routine without excessive reassurance and without showing extreme reactions |

For example, the student’s schedule may change, maybe there is an assembly or PE class has been cancelled. The student is able to accept the change and go on with their day without a noticeable negative reaction – it’s okay to show some disappointment or confusion, but it’s not an extreme reaction |

Social Language and Conversational Adaptation Able to stay on topic providing appropriate comments and questions without switching topic abruptly |

For example, the student can provide 2-3 comments and/or questions regarding a given topic |

Social Reasoning Demonstrates difficulty seeing the “whole picture” during lectures and shows difficulty grasping main idea or key points and excessively focuses on irrelevant details. |

For example, during class discussion, student may write down everything the teacher says or is unable to highlight the most relevant and meaningful key points. |

Cognitive Flexibility Excessively insists on fairness |

For example, every week students line up alphabetically to go to lunch. A student may insist that this is not fair and that they should rotate the order each week. The teacher explains to the student that she understands what he/she is saying but it’s just too difficult to organize and change every week, the student will not let it go and insists on the line up being “fair” |

Administration of the Rating Scale

Examiner Qualifications

Professionals who are formally trained in the ethical administration, scoring, and interpretation of assessment tools and who hold appropriate educational and professional credentials may administer the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale. Qualified examiners include speech-language pathologists, school psychologists, special education diagnosticians and other professionals representing closely related fields. It is a requirement to read and become familiar with the administration, recording, and scoring procedures before using this rating scale and asking parents and teachers to complete the rating scales.

Confidentiality Requirements

As described in Standard 6.7 of the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (AERA et al., 2014), it is the examiner’s responsibility to protect the security of all testing material and ensure confidentiality of all testing results.

Eligibility for Testing

The IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale is appropriate to use for individuals between the ages of 5-0 and 21-0 years of age. This rating scale is designed for individuals who are suspected of or who have been previously diagnosed with a speech sound disorder. The rating scale also addresses the potential impact that an articulation or phonological disorder may have on a chil

Easy to Follow Steps

Step 1

Complete the CLINICIAN online rating form that will calculate student age and raw scores for you!

Step 2

Email or Text links to the online rating form to TEACHER(S) and PARENT(S), and get the results back by email (or printed pdfs).

Step 3

Email or Text links to the online rating form to TEACHER(S) and PARENT(S), and get the results back by email (or printed pdfs).

Theoretical Background of the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale

Pragmatic language, or social communication, refers to the ability to use both verbal and nonverbal language across various contexts and social situations. Pragmatics differs from the structural aspects of language that are considered to be independent of context, such as phonology, syntax, and semantics (Camarata & Gibson, 1999). Pragmatic language ties together all parts of language comprehension and oral expression and allows for effective communication to take place. When deficits in social language occur, there may be significant disruptions in communication (Norbury, 2014). These disruptions may impact a child’s ability to function at home, school, and with their peers (Russell, 2007; Russell & Grizzle, 2008). Simply put, pragmatics can be defined as an individual knowing when to say what to whom and how much (Hymes, 1971). Of course, this is a very broad, simplistic definition and pragmatics is composed of much more. Prutting and Kirchner (1987) describe pragmatic language skill as the ability to use language in various situations for a specific purpose.

When students present with social language deficits, they may have difficulty with greetings, turn-taking skills, introduction of new topics, topic maintenance, the ability to respond to verbal cues from others, the ability to code-switch or change a message to the needs of a listen, or the ability to understand sarcasm, jokes, and metaphors (Bignell & Cain 2007; Camarata & Gibson, 1999; Perkins, 2010, Russell, 2007). In addition, students may have difficulty with non-verbal language such as maintaining adequate eye-contact and gaze, body language, micro expressions of the face, gestures, and intonation or prosody (Prutting & Kirchner, 1987). When pragmatic language impairments go undiagnosed and untreated, there can be a large, negative psychosocial impact for the child. Social language deficits can impact a child’s academic success as well as their mental health status, social integration, and future employment prospects and occupation success (Whitehouse, Watt, Line, & Bishop, 2009). There is a clear need for the identification of students with pragmatic language difficulties, because without appropriate intervention and treatment, quality communication cannot occur, which can result in long-term psychosocial problems.

Pragmatic language deficits affect many of our students, many who present with high functioning autism and social communication disorder. By observing student’s in their natural environment and assessing their social language skills, diagnoses can be made and interventions can be implemented. The identification of students who present with pragmatic language impairments cannot be understated. Pragmatics required specialized education and support.

Standardization and Normative Information

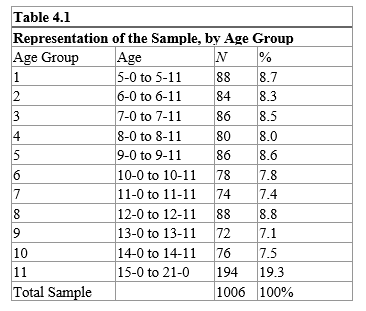

The normative data for the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale is based on the performance of 1006 examinees across 11 age groups (shown in Table 4.1) from 17 states across the United States of America (Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Ohio, Minnesota, Florida, New York, Pennsylvania, Florida, South Carolina, Texas, Washington).

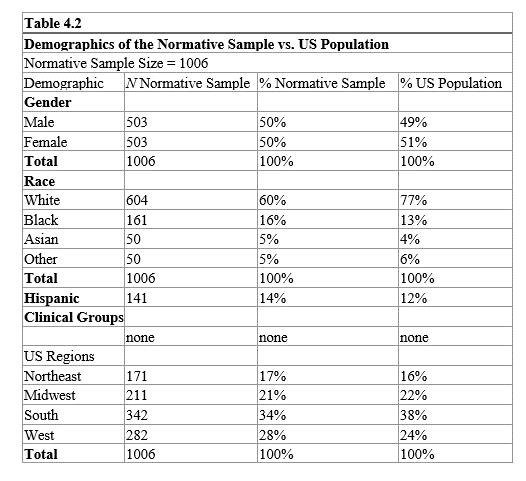

The data was collected throughout the 2016-2020 school years by 34 state licensed speech-language pathologists (SLPs). The SLPs were recruited through Go2Consult Speech and Language Services, a certified special education staffing company. All standardization project procedures were reviewed and approved by IntegReview IRB, an accredited and certified independent institutional review board. To ensure representation of the national population, the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale standardization sample was selected to match the US Census data reported in the ProQuest Statistical Abstract of the United States (ProQuest, 2017). The sample was stratified within each age group by the following criteria: gender, race or ethnic group, and geographic region. The demographic table below (Table 4.2) specifies the distributions of these characteristics and shows that the normative sample is nationally representative.

Criteria for inclusion in the normative sample

A good assessment is one that yields results that will benefit the individual being tested or society as a whole (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education [AERA, APA, and NCME], 2014). One way we can tell if an assessment is a good test, is if it includes adequate norms. Previous research has suggested that utilizing a normative sample can be beneficial in the identification of a disability and that the inclusion of children with disabilities may negatively impact the test’s ability to differentiate between children with disorders and children who are typically developing (Peña, Spaulding, & Plante, 2006). Since the purpose of the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale is to help to identify students who present with social communication deficits, it was critical to exclude students from the normative sample who have diagnoses that are known to influence social communication (Peña, Spaulding, & Plante, 2006). Students who had previously been diagnosed with a specific language impairment or learning disability were not included in the normative sample. Further, students were excluded from the normative sample if they were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, hearing loss, neurological disorders, or genetically syndromes. Students who present with articulation disorders or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders were allowed to be included in the normative sample, as long as there was no co-occurring pragmatic language disorder. To sum up, in order for students to be included in the present normative sample, students must have met criteria of having normal language development, and show no evidence of a social language communication disorder. Students used in the present normative sample had no other diagnosed disabilities and were not receiving speech and language support or any other services. Thus, the normative sample for the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale provides an appropriate comparison group (i.e., a group without any known disorders that might affect social communication) against which to compare students with suspected disorders.

*Note: The IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale is designed for students who are native speakers of English and/or are English language learners (ELL) who have demonstrated a proficiency in English based on state testing scores and school district language evaluations. Additionally, students who were native English speakers and also spoke a second language were included in this sample.

Norm-referenced testing is a method of evaluation where an individual’s scores on a specific test are compared to scores of a group of test-takers (e.g., age norms) (AERA, APA, and NCME, 2014). Clinicians can compare clinician, teacher, and parent ratings on the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale to this normative sample to determine whether a student is scoring within normal limits or, if their scores are indicative of a social communication disorder. Administration, scoring, and interpretation of the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale must be followed in order to make comparisons to normative data. This manual provides instructions to guide examiners in the administration, scoring, and interpretation of the rating scale.

Validity and Reliability

This section of the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale manual provides information on the psychometric characteristics of validity and reliability. Validity helps establish how well a test measures what it is supposed to measure and reliability represents the consistency with which an assessment tool measures certain ability or skill. The first half of this chapter will evaluate content, construct, criterion, and clinical validity of the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale. The latter half of the chapter will review the consistency and stability of the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale scores, in addition to test retest and inter-rater reliability.

Validity

When considering the strength of a test, one of the most important aspects to consider is validity. Content validity refers to whether the test provides the clinician with accurate information on the ability being tested. Specifically, content validity measures whether or not the test actually assesses what it says it’s suppose to. According to McCauley and Strand (2008), there should be a justification of the methods used to choose content, expert evaluation of the test’s content, and an item analysis.

Content-oriented evidence of validation addresses the relationship between a student’s learning standards and the test content. Specifically, content-sampling issues take a look at whether cognitive demands of a test are reflective of the student’s learning standard level. Additionally, content sampling may address whether the test avoids inclusion of features irrelevant to what the test item is intended to target.

Single-cut Scores

It is often common practice to use single cut scores (e.g., -1.5 standard deviations) to identify disorders, however, this is not evidence-based and there is actually evidence that advises against using this practice (Spaulding, Plante, & Farinella, 2006). When using single cut scores (e.g., -1.5 SD, -2.5 SD, etc.), we may under identify students with impairments on tests for which the best-cut score is higher and over identify students’ impairments on tests for which the best-cut score is lower. Additionally, using single cut scores may go against IDEA’s (2004) mandate, which states assessments must be valid for the purpose for which they are used.

Sensitivity and Specificity

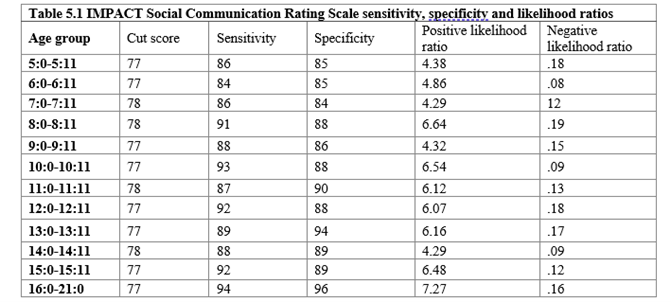

Table 5.1 shows the cut scores needed to identify social communication disorders within each age range. Additionally, this table demonstrates the sensitivity and specificity information that indicates the accuracy of identification at these cut scores. Sensitivity and specificity are diagnostic validity statistics that explain how well a test performs. Vance and Plante (1994) set forth the standard that for a language assessment to be considered clinically beneficial, it should reach at least 80% sensitivity and specificity.

Thus, strong sensitivity and specificity (i.e., 80% or stronger) is needed to support the use of a test in its identification of the presence of a disorder or impairment. Sensitivity measures how well the assessment will accurately identify those who truly have a social language disorder (Dollaghan, 2007). If sensitivity is high, this indicates that the test is highly likely to identify the pragmatic language disorder, or, there is a low chance of “false positives.” Specificity measures the degree to which the assessment will accurately identify those who do not have a pragmatic language disorder, or how well the test will identify those who are “typically developing” (Dollaghan, 2007).

Content Validity

The validity of a test determines how well the test measures what it purports to measure. Validity can take various forms, both theoretical and empirical. This can often compare the instrument with other measures or criteria, which are known to be valid (Zumbo, 2014). For the content validity of the test, expert opinion was solicited. Twenty-nine speech language pathologists (SLPs) reviewed the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale. All SLPs were licensed in the state of California, held the Clinical Certificate of Competence from the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, and had at least 5 years of experience in assessment of children with autism and social communication deficits. Each of these experts was presented with a comprehensive overview of the rating scale descriptions, as well as rules for standardized administration and scoring. They all reviewed 6 full-length administrations. Following this, they were asked 30 questions related to the content of the rating scale and whether they believed the assessment tool to be an adequate measure of social communication skills. For instance, their opinion was solicited regarding whether the questions and the raters’ responses properly evaluated the impact of social communication skills on educational performance and social interaction. The reviewers rated each rating scale on a decimal scale. All reviewers agreed that the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale is a valid informal observational measure to evaluate social communication skills and to determine the impact on educational performance and social interaction, in students who are between the ages of 5 and 21 years old. The mean ratings for the Clinician, Teacher, and Parent rating scales were 28.7±0.9, 27.3±0.8, 27.9±1.0, respectively.

Construct Validity

Developmental Progression of Scores

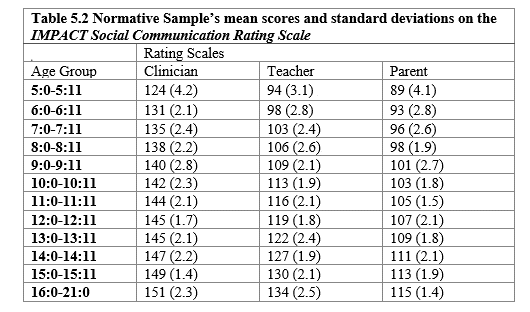

Pragmatic language is developmental in nature and a skill that changes overtime and with age. Mean scores for examinees should increase with chronological age, demonstrating age differentiation. Mean scores and standard deviations for the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale are divided into eleven age intervals displayed in Table 5.2.

Criterion Validity

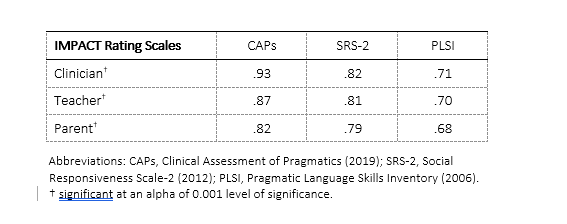

In assessing criterion validity, the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale was correlated to other measures of social communication such as the Clinical Assessment of Pragmatics (CAPs; Lavi, 2019), the Social Responsiveness Scale -2 (SRS-2; Constantino & Gruber, 2012), and the Pragmatic Language Skills Inventory (PLSI; Gilliam & Miller, 2006). Time between test administrations ranged from the same day to five days.

The concurrent validity was assessed using Pearson’s correlation among all measures. Correlation coefficients of ≥0.7 are recommended for same-construct instruments, while moderate correlations of ≥0.4 to ≤0.70 are acceptable. The level of significance was set at p≤0.05. When assessing validity, the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale was substantially correlated with the CAPs (2019) and the SRS-2 (2012): 0.93, and 0.82 respectively, p<0.001. The correlations are the lowest with the PLSI (2006) (Table 5.3). While there is an apparent relationship between performance on all three measures, the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale evaluates social language from a conceptually different framework.

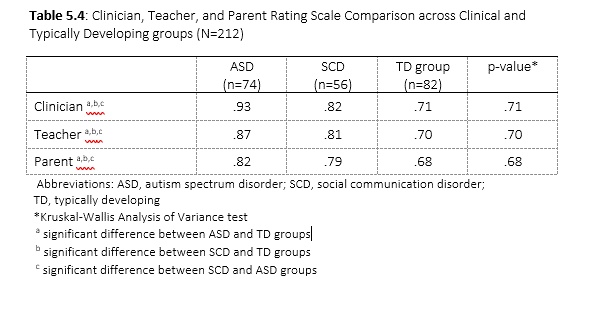

Group Differences

Since a social communication assessment tool is designed to identify those examinees with social language deficits, it would be expected that individuals identified as likely to exhibit pragmatic language deficits would score lower than those who are typically developing. The mean for the outcome variables (Clinician, Teacher, and Parent ratings) were compared among the two clinical groups and the typically developing group of examinees using Kruskal Wallis analysis of variance (ANOVA). The level of significance was set at p≤0.05. Table 5.4 reviews the ANOVA, which reveals a significant difference between all three groups.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria for the Group Differences Study

Typically developing participants were selected based on the following criteria: 1) exhibited hearing sensitivity within normal limits; 2) presented with age-appropriate speech and language skills; 3) successfully completed each school year with no academic failures; and 4) attended public school and placed in general education classrooms. Typically developing participants were excluded if they presented with conditions as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-V; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) as having a diagnosis of mental health problems such as clinical disorders, personality disorders, and general medical conditions.

Inclusion criteria for the autism spectrum disorder (ASD) group was: 1) having a current diagnosis within the autism spectrum disorder as defined by the DSM- V (2013) (based on medical records and school-based special education eligibility criteria); and 2) currently attending a local public school, and enrolled in the general education classroom for at least 3 hours per day. Participants were excluded if they presented with comorbid conditions as defined by a DSM- V (2013) diagnosis of mental health problems such as clinical disorders, personality disorders, and general medical conditions.

Lastly, the inclusion criteria for the social communication disorder (SCD) group was: 1) having a current diagnosis within the social communication disorder as defined by the DSM- V (2013) (based on medical records, school-based special education eligibility criteria, obtaining a score of 76 or below on the Clinical Assessment of Pragmatics test, and displaying inappropriate or inadequate usage of pragmatic language as documented by medical or special educational records); 2) being enrolled in the general education classroom for at least 4 hours per day. Students from the SCD group were excluded from the study if the following were identified: 1) intellectual disability, learning disability, emotional disturbance; 2) comorbid conditions where the student had a DSM- V (2013) diagnosis of mental health problems including clinical disorders, personality disorders, and general medical conditions.

Standards for fairness

Standards of fairness are crucial to the validity and comparability of the interpretation of test scores (AERA, APA, and NCME, 2014). The identification and removal of construct-irrelevant barriers maximizes each test- taker’s performance, allowing for skills to be compared to the normative sample for a valid interpretation. Test constructs and individuals or subgroups of those who the test is intended for must be clearly defined. In doing so, the test will be free of construct-irrelevant barriers as much as possible for the individuals and/or subgroups the test is intended for. It is also important that simple and clear instructions are provided.

Response Bias

A bias is defined as a tendency, inclination, or prejudice toward or against something or someone. For example, if you are interviewing for a new employer and asked to complete a personality questionnaire, you may answer the questions in a way that you think will impress the employer. These responses will of course impact the validity of the questionnaire.

Responses to questionnaires, tests, scales, and inventories may also be biased for a variety of reasons. Response bias may occur consciously or unconsciously, it may be malicious or cooperative, self-enhancing or self-effacing (Furr, 2011). When response bias does occur, the reliability and validity of our measures will be compromised. Diminished reliability and validity will in turn impact decisions we make regarding our students (Furr, 2011). Thus, psychometric damage may occur because of response bias.

Types of Response Biases

Acquiescence Bias (“Yea-Saying and Nay-Saying”) refers to when an individual consistently agrees or disagrees with a statement without taking into account what the statement means (Danner & Rammstedt, 2016).

Extremity Bias refers to when an individual consistently over or underuses “extreme” response options, regardless of how the individual feels towards the statement (Wetzel, Lüdtke, Zettler, & Bohnke, 2015).

Social desirability Bias refers to when an individual responds to a statement in a way that exaggerates his or her own positive qualities (Paulhus, 2002).

Malingering refers to when an individual attempts to exaggerate problems, or shortcomings (Rogers, 2008). Random/careless responding refers to when an individual responds to items with very little attention or care to the content of the items (Crede, 2010).

Guessing refers to when the individual is unaware of or unable to gage the correct answer regarding their own or someone else’s ability, knowledge, skill, etc. (Foley, 2016).

In order to protect against biases, balanced scales are utilized. A balanced scale is a test or questionnaire that includes some items that are positively keyed and some items that are negatively keys. For example, the Impact Social Communication Rating Scale items are rated on a 4-point scale (“never,” “sometimes,” “often,” and “typically”). Now, imagine if we ask a teacher to answer the following two items regarding one of their students:

- The student appears confident and comfortable when socializing with peers.

- The student does not appear overly anxious and fidgety around group of peers.

Both of these items are positively keyed because a positive response indicates a stronger level of social language skills. To minimize the potential effects of acquiescence bias, the researcher may revise one of these items to be negatively keyed. For example:

- The student appears confident and comfortable when socializing with peers.

- The student appears overly anxious and fidgety around group of peers.

Now, the first item is keyed positively and the second item is keyed negatively. The revised scale, which represents a balanced scale, helps control acquiescence bias by including one item that is positively keyed and one that is negatively keyed. If the teacher responded highly on both items, the teacher may be viewed as an acquiescent responder (i.e., the teacher is simply agreeing to items without regard for the content). If the teacher responds high on the first item, and responds low on the second item, we know that the teacher is reading each test item carefully and responding appropriately.

For a balanced scale to be useful, it must be scored appropriately, meaning the key must accommodate the fact that there are both positively and negatively keyed items. To achieve this, the rating scale must keep track of the negatively keyed items and “reverse the score.” Scores are only reversed for negatively keyed items. For example, on the negatively keyed item above, if the teacher scored a 1 (“never”) the score should be converted to a 4 (“typically”) and if the teacher scored a 2 (“sometimes”) the score should be converted to a 3 (“often”). Similarly, the researcher recodes responses of 4 (“typically”) to 1 (“never”) and 3 (“often”) to 2 (“sometimes”). Balanced scales help researchers differentiate between acquiescent responders and valid responders. Therefore, test users can be confident that the individual reporting is a reliable and valid source.

Inter-rater Reliability

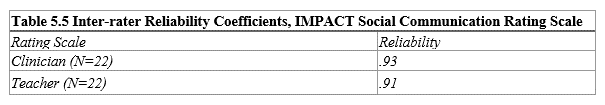

Inter-rater reliability measures the extent to which consistency is demonstrated between different raters with regard to their scoring of examinees on the same instrument (Osborne, 2008). For the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale, inter-rater reliability was evaluated by examining the consistency with which the raters are able to follow the test scoring procedures. Two clinicians, two teachers, and two caregivers simultaneously rated students. The results of the scorings were correlated. The coefficients were averaged using the z-transformation method. The resulting correlations for the subtests are listed in Table 5.5.

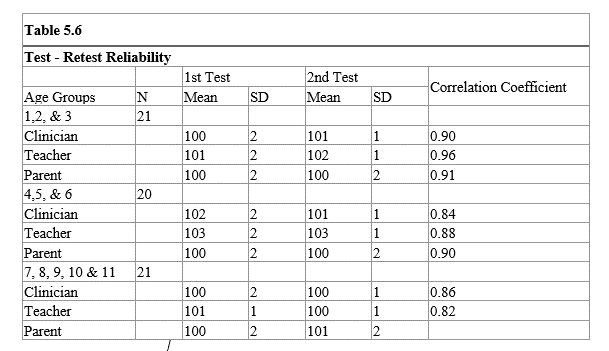

Test-Retest Reliability

This is a factor determined by the variation between scores or different evaluative measurements of the same subject taking the same test during a given period of time. If the test is a strong instrument, this variation would be expected to be low (Osborne, 2008). The IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale was completed with 62 randomly selected examinees, ages 5-0 through 21-0 over two rating periods. The interval between the two periods ranged from 16 to 20 days. To reduce recall bias, the examiners did not inform the raters at the time of the first rating session that they would be rating again. All subsequent ratings were completed by the same examiners who administered the test the first time. The results are listed in Table 5.6. The test-retest coefficients for the three rating scales were all greater than .80 indicating strong test-retest reliability for the IMPACT Social Communication Rating Scale.